Poster Presentation ESA-SRB-ANZOS 2025 in conjunction with ENSA

Hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state: A systematic review of management guidelines and their evidence (#113)

Hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS) is a life-threatening endocrine emergency. HHS occurs less frequently than diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) (1), but has a higher mortality (2), with reported mortality rates of 10-50% (3-7). HHS management is largely varied in clinical practice due to a lack of high-quality evidence. This systematic review aims to compare international guidelines and their underlying evidence base in HHS management. MEDLINE, Embase and Emcare databases were searched, and references of relevant papers were reviewed, identifying 363 papers, of which 7 met the inclusion criteria.

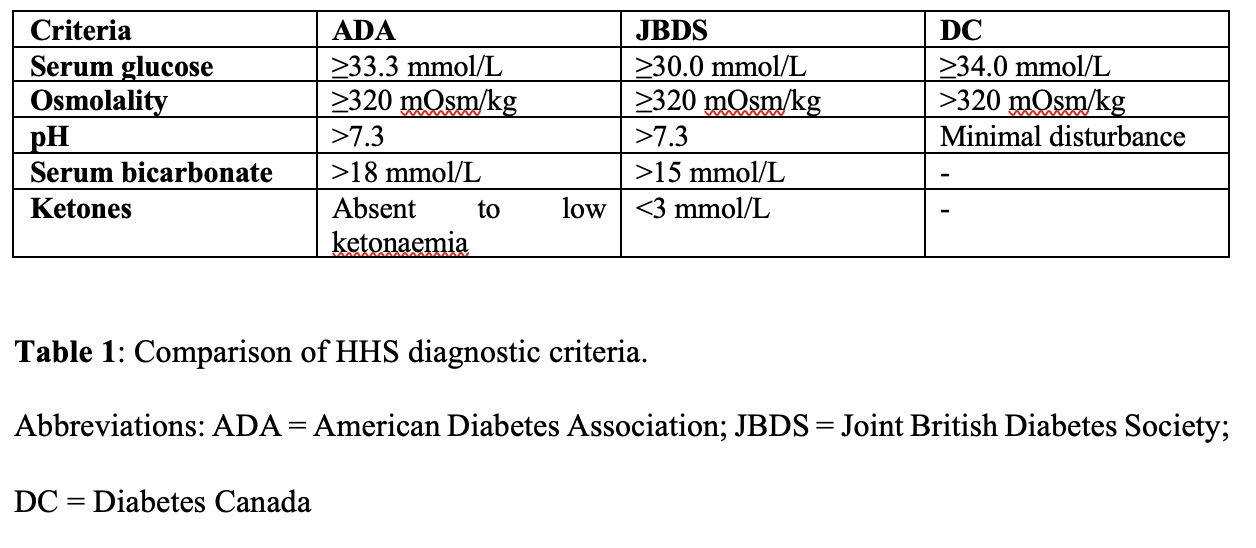

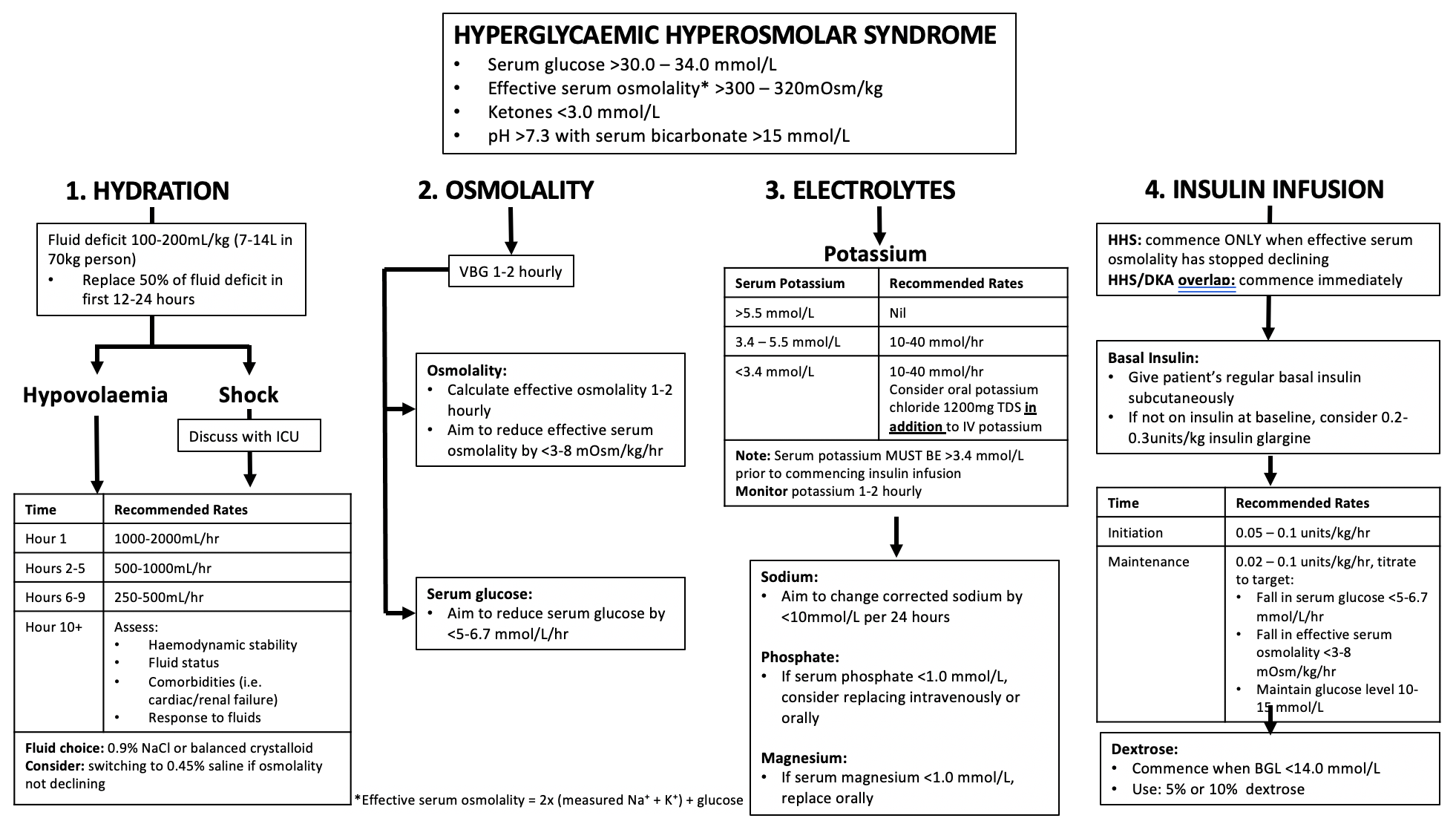

The hallmark features of HHS include profound hypovolaemia, extreme hyperglycaemia, and hyperosmolality (7, 8), although specific diagnostic criteria vary among guidelines from glucose ≥33.3mmol/L and osmolality ≥320mOsm/kg (American Diabetes Association [ADA] and Diabetes Canada [DC]) (7, 9) to glucose ≥30.0mmol/L with osmolality ≥320mOsm/kg (Joint British Diabetes Society [JBDS]) (10) (Table 1). There is also significant heterogeneity in HHS management (Figure 1). The ADA and DC guidelines recommend correction of serum osmolality <3mOsm/kg/hr (7, 9), whereas the JBDS accept osmolality change of 3-8mOsm/kg/hr (10). ADA guidelines suggest 0.9% normal saline at 15-20mL/kg/hr or 1-1.5L/hr (7), whereas JBDS guidelines suggest replacing ~50% of the estimated fluid loss within the first 12 hours (10). The ADA and DC guidelines recommend a fixed rate insulin infusion of 0.1units/kg/hr (7, 9). The JBDS guidelines recommend 0.05units/kg/hr, increasing by 1.0units/hr as required (10).

Current HHS guidelines are consensus-based rather than evidence-based because no randomised controlled trials exist. HHS management is largely driven by evidence derived from small studies in patients with DKA, rather than specific HHS trials. Further high-quality prospective studies specific to HHS are required to standardise diagnosis and optimise management.

- Benoit SR, Hora I, Pasquel FJ, Gregg EW, Albright AL, Imperatore G. Trends in Emergency Department Visits and Inpatient Admissions for Hyperglycemic Crises in Adults With Diabetes in the U.S., 2006-2015. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(5):1057-64.

- Pasquel FJ, Tsegka K, Wang H, Cardona S, Galindo RJ, Fayfman M, et al. Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Isolated or Combined Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State: A Retrospective, Hospital-Based Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(2):349-57.

- MacIsaac RJ, Lee LY, McNeil KJ, Tsalamandris C, Jerums G. Influence of age on the presentation and outcome of acidotic and hyperosmolar diabetic emergencies. Intern Med J. 2002;32(8):379-85.

- Chung ST, Perue GG, Johnson A, Younger N, Hoo CS, Pascoe RW, et al. Predictors of hyperglycaemic crises and their associated mortality in Jamaica. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;73(2):184-90.

- Fadini GP, de Kreutzenberg SV, Rigato M, Brocco S, Marchesan M, Tiengo A, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of the hyperglycemic hyperosmolar non-ketotic syndrome in a cohort of 51 consecutive cases at a single center. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94(2):172-9.

- Chen HF, Wang CY, Lee HY, See TT, Chen MH, Jiang JY, et al. Short-term case fatality rate and associated factors among inpatients with diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state: a hospital-based analysis over a 15-year period. Intern Med. 2010;49(8):729-37.

- Umpierrez GE, Davis GM, ElSayed NA, Fadini GP, Galindo RJ, Hirsch IB, et al. Hyperglycemic Crises in Adults With Diabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(8):1257-75.

- Long B, Willis GC, Lentz S, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M. Diagnosis and Management of the Critically Ill Adult Patient with Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State. J Emerg Med. 2021;61(4):365-75.

- Goguen J, Gilbert J. Hyperglycemic Emergencies in Adults. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42 Suppl 1:S109-s14.

- Mustafa OG, Haq M, Dashora U, Castro E, Dhatariya KK. Management of Hyperosmolar Hyperglycaemic State (HHS) in Adults: An updated guideline from the Joint British Diabetes Societies (JBDS) for Inpatient Care Group. Diabet Med. 2023;40(3):e15005.